San Bruno, California

San Bruno | |

|---|---|

| Etymology: from Spanish 'St. Bruno' | |

| Motto: "City with a Heart"[1] | |

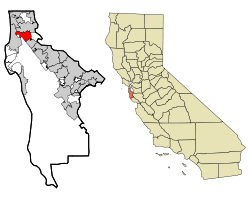

Location in San Mateo County and the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 37°37′31″N 122°25′31″W / 37.62528°N 122.42528°W[2] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | San Mateo |

| Region | San Francisco Bay Area |

| Region | Northern California |

| Incorporated | December 23, 1914[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager[4] |

| • Mayor | Rico E. Medina[5] |

| Area | |

• Total | 5.49 sq mi (14.22 km2) |

| • Land | 5.49 sq mi (14.22 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 20 ft (6 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 43,908 |

| • Density | 7,799.2/sq mi (3,011.29/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 94066, 94067, 94096, 94098 |

| Area code | 650 |

| FIPS code | 06-65028 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277616, 2411778 |

| Website | sanbruno |

San Bruno (from Spanish 'St. Bruno') is a city in San Mateo County, California, United States, incorporated in 1914. The population was 43,908 at the 2020 United States Census. The city is between South San Francisco and Millbrae, adjacent to San Francisco International Airport and Golden Gate National Cemetery; it is approximately 12 miles (19 km) south of Downtown San Francisco.

Geography

[edit]The city is located between South San Francisco and Millbrae, adjacent to San Francisco International Airport to the east and Golden Gate National Cemetery to the northwest. It is approximately 12 miles (19 km) south of Downtown San Francisco.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 5.5 square miles (14 km2), all of it land. The city spreads from the mostly flat lowlands near San Francisco Bay into the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains, which rise to more than 600 feet (180 m) above sea level in Crestmoor and more than 700 feet (210 m) above sea level in Portola Highlands. San Bruno City Hall sits at an official elevation of 41 feet (12 m) above sea level.

Portions of Mills Park, Crestmoor, and Rollingwood are very hilly, featuring canyons and ravines. Creeks, many of them now in culverts, flow from springs in the hills toward San Francisco Bay. Just west of Skyline Boulevard and outside of city limits is San Andreas Lake, which got its name from the San Andreas Fault. The lake is one of several reservoirs used by the San Francisco Water Department, providing water to San Francisco and several communities in San Mateo County, including San Bruno west of I-280.

Climate

[edit]

| San Bruno, California | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

San Bruno has a mild Mediterranean climate characterized by mild to warm, dry summers and cool, wet winters. San Bruno has much milder temperatures than most of the state. Owing to its relatively mild temperatures, the city's climate closely resembles that of an oceanic climate. Since 1927, the National Weather Service (formerly the U.S. Weather Bureau) has maintained a weather station at the nearby San Francisco International Airport (formerly Mills Field). According to the official records, January is the coldest month with an average high of 55.9 °F (13.3 °C) and an average low of 42.9 °F (6.1 °C (43.0 °F)reezing temperatures occur on an average of only 1.3 days annually. The coldest winter temperature on record was 20 °F (−7 °C) on December 11, 1932, a day on which 1 inch (2.5 cm) of snow also fell. A week-long cold spell in December 1972 caused hard freezes throughout the area, damaging trees and plants and causing some water pipes to break; the temperature dropped as low as 24 °F (−4 °C) at the airport and 20 °F (−7 °C) in Crestmoor, which also reported snow flurries several times that week. There was 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) of snow at the airport on January 21, 1962, with several inches falling in the hills.

September is the warmest month with an average high of 72.7 °F (22.6 °C) and an average low of 55.1 °F (12.8 °C). Temperatures exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on an average of 4.0 days annually. Fog and low overcast are common during the night and morning hours in the summer months, which are generally very dry except for occasional light drizzle from the fog. On rare occasions moisture moving up from tropical storms has produced thunderstorms or showers in the summer. Gusty westerly winds are also common in the afternoon during the summer. The highest summer temperature was 106 °F (41 °C) on June 14, 1961, breaking a record of 104 °F (40 °C) set in June 1960. A high of 105 °F (41 °C) was recorded on July 17, 1988, and a high of 104 °F (40 °C) was recorded on September 1, 2017. Until August 1, 1993, it had never reached 100 °F (38 °C) in August, which is one of the foggier months in the area. Due to thermal inversions, summer temperatures in the higher hills are often much higher than at the airport.

Thunderstorms occur several times a year, mostly during the winter months, but are usually quite brief. Total annual precipitation, most of which falls from November to April, ranges from 20.11 inches (511 mm) at the nearby National Weather Service station at San Francisco International Airport to over 32 inches (810 mm) in the higher hills (according to observations by Gayle Rucker for the Army Corps of Engineers and Robert E. Nylund for the U.S. Geological Survey from 1962 to 1985). Nylund also took temperature observations for several years and published weekly weather reports in the San Bruno Herald from 1966 to 1969, which were included in official reports for the Golden Gate National Cemetery. The annual average days with measurable precipitation is 65.2 days. The most rainfall in a month at the airport was 13.64 inches (346 mm) in February 1998, and the most rainfall in 24 hours was 5.59 inches (142 mm) on January 4, 1982. Nylund reported 6.09 inches (155 mm) in Crestmoor during a 24-hour period in January 1967. Winter storms are often accompanied by strong southerly winds.[10]

| Climate data for San Francisco International Airport | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

77 (25) |

85 (29) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

99 (37) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

106 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 55.8 (13.2) |

59.1 (15.1) |

61.2 (16.2) |

63.8 (17.7) |

66.7 (19.3) |

70.0 (21.1) |

71.4 (21.9) |

72.0 (22.2) |

73.4 (23.0) |

70.2 (21.2) |

62.9 (17.2) |

56.4 (13.6) |

65.2 (18.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 49.2 (9.6) |

52.0 (11.1) |

53.7 (12.1) |

55.8 (13.2) |

58.5 (14.7) |

61.4 (16.3) |

62.7 (17.1) |

63.5 (17.5) |

64.1 (17.8) |

61.1 (16.2) |

55.2 (12.9) |

49.8 (9.9) |

57.3 (14.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 42.6 (5.9) |

45.0 (7.2) |

46.2 (7.9) |

47.7 (8.7) |

50.2 (10.1) |

52.8 (11.6) |

54.1 (12.3) |

55.0 (12.8) |

54.8 (12.7) |

52.1 (11.2) |

47.4 (8.6) |

43.3 (6.3) |

49.3 (9.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 26 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

31 (−1) |

36 (2) |

39 (4) |

43 (6) |

44 (7) |

45 (7) |

41 (5) |

37 (3) |

31 (−1) |

24 (−4) |

24 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.31 (109) |

3.58 (91) |

2.88 (73) |

1.38 (35) |

0.39 (9.9) |

0.13 (3.3) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.04 (1.0) |

0.17 (4.3) |

1.00 (25) |

2.31 (59) |

3.73 (95) |

19.94 (506.01) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 64 |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[11] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 1,562 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,610 | 131.1% | |

| 1940 | 6,519 | 80.6% | |

| 1950 | 12,478 | 91.4% | |

| 1960 | 29,063 | 132.9% | |

| 1970 | 36,254 | 24.7% | |

| 1980 | 35,417 | −2.3% | |

| 1990 | 38,961 | 10.0% | |

| 2000 | 40,165 | 3.1% | |

| 2010 | 41,114 | 2.4% | |

| 2020 | 43,908 | 6.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States Census[13] reported that San Bruno had a population of 41,114. The population density was 7,505.0 inhabitants per square mile (2,897.7/km2). The racial makeup of San Bruno was 20,350 (49.5%) White, 942 (2.3%) African American, 246 (0.6%) Native American, 10,423 (25.4%) Asian, 1,377 (3.3%) Pacific Islander, 5,075 (12.3%) from other races, and 2,701 (6.6%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 12,016 persons (29.2%).

The Census reported that 40,716 people (99.0% of the population) lived in households, 316 (0.8%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 82 (0.2%) were institutionalized.

There were 14,701 households, out of which 4,831 (32.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 7,364 (50.1%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 1,830 (12.4%) had a female householder with no husband present, 850 (5.8%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 764 (5.2%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 123 (0.8%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 3,660 households (24.9%) were made up of individuals, and 1,119 (7.6%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.77. There were 10,044 families (68.3% of all households); the average family size was 3.31.[citation needed]

The population was spread out, with 8,632 people (21.0%) under the age of 18, 3,577 people (8.7%) aged 18 to 24, 12,038 people (29.3%) aged 25 to 44, 11,653 people (28.3%) aged 45 to 64, and 5,214 people (12.7%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.1 males.

There were 15,356 housing units at an average density of 2,803.1 units per square mile (1,082.3 units/km2), of which 8,938 (60.8%) were owner-occupied, and 5,763 (39.2%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.1%; the rental vacancy rate was 3.9%. 24,712 people (60.1% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 16,004 people (38.9%) lived in rental housing units.

|

2000

[edit]As of the census[15] of 2008, there were 42,401 people, 15,486 households, and 10,561 families residing in the city. The population density was 8,353.6 inhabitants per square mile (3,225.3/km2). There were 16,403 housing units at an average density of 3,742.6 units per square mile (1,445.0 units/km2).

There were 15,486 households, out of which 35.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.8% were married couples living together, 12.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.4% were non-families. 28.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.72 and the average family size was 4.29.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 25.0% under the age of 18, 11.2% from 18 to 24, 35.5% from 25 to 44, 22.1% from 45 to 64, and 9.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.1 males.

The median household income for the city was $60,081, and the median income for a family was $69,251 (these figures had risen to $71,869 and $80,401 respectively as of a 2008 estimate[16]). Males had a median income of $47,843 versus $39,851 for females. The per capita income for the city was $25,360. About 5.1% of families and 7.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.8% of those under age 18 and 6.5% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

[edit]

The current mayor of San Bruno is Rico E. Medina, who began his term as mayor on December 12, 2017. He has previously been a council member.[17] The previous mayor of San Bruno was Jim Ruane,[5] who was first elected in 2009 and served until December 2017. The mayor before Jim Ruane was Larry Franzella, who was first elected November 1999 and was reelected through November 2009.[18] Bob Marshall, "Mr. San Bruno", served as mayor from 1980 to 1992.[19] San Bruno is one of the few cities in San Mateo County with an independently elected mayor.[20]

In the California State Legislature, San Bruno is in the 13th Senate District, represented by Democrat Josh Becker, and is split between the 21st Assembly District, represented by Democrat Diane Papan and the 19th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Phil Ting.[21]

In the United States House of Representatives, San Bruno is in California's 15th congressional district, represented by Democrat Kevin Mullin.[22]

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, San Bruno has 22,808 registered voters. Of those, 11,856 (52%) are registered Democrats, 3,051 (13.4%) are registered Republicans, and 6,993 (30.1%) have declined to state a political party.[23]

Parks

[edit]

San Bruno City Park, bordered by Crystal Springs Avenue and El Crystal School, is the largest municipal park. It offers shaded walkways and hiking trails, picnic tables, a playground, a small ballpark, a municipal swimming pool, and a recreation center that includes an indoor basketball court once used for training by the San Francisco Warriors basketball team.[24] There are smaller municipal parks in other parts of the city.

Junipero Serra County Park, also accessible from Crystal Springs Avenue, is a 100-acre (40 ha) park owned by San Mateo County which includes numerous hiking trails, as well as picnic shelters, barbecue pits, and picnic tables.[25] The wilderness area was named for Junípero Serra, a Franciscan friar who founded many of the Spanish missions in California during the eighteenth century; Serra regularly passed through what is now San Bruno whenever he visited the mission at San Francisco. The park is administered by the San Mateo County Parks and Recreation Department, which charges a $6 entry fee for vehicles from the entrance off Crystal Springs Road; there are two pedestrian entrances, one from San Bruno City Park and the other from Helen Drive.

Education

[edit]The city is served by the San Bruno Park School District which operates five elementary schools, and one intermediate school; in 1970, the school district had an enrollment of 4,829, and as of 2013[update] was closer to 2,700.[26] San Mateo Union High School District also serves the city, and most students who attend secondary public education attend Capuchino High School, the only high school in the community after Crestmoor High School was closed in 1980.[26] The city's main library is part of the Peninsula Library System. Skyline College, a community college that is part of the San Mateo Community College District (SMCCD), is located in San Bruno.

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]San Bruno was the location of the Ohlone village Urebure. It was explored in November 1769 by a Spanish expedition led by Gaspar de Portolà. Later, more extensive explorations by Bruno de Heceta resulted in the naming of San Bruno Creek after St. Bruno of Cologne, the founder of a medieval monastic order. This creek apparently later gave its name to the community.

With the establishment of the San Francisco de Asís (St. Francis of Assisi) mission, much of the area became pasture for the mission livestock. Following the decline of the missions, the area became part of Rancho Buri Buri granted to José de la Cruz Sánchez, the eleventh Alcalde (mayor) of San Francisco. After Jose Antonio Sanchez died, his heirs divided the Rancho and sold it off.[27] Dairy farms later became common in much of the area.

The city began as Clarks's Station,[28] a stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach route, utilizing an inn built in 1849, which was initially called Thorp's Place and later Uncle Tom's Cabin or 14 Mile House.[29] The inn was demolished in 1949 and replaced with a Lucky's supermarket (now a Walgreens drugstore, on the corner of El Camino Real and Crystal Springs Avenue). Gus Jenevein (for whom Jenevein Avenue was named) built another landmark called San Bruno House, which burned several times and was not rebuilt after the third fire. A few homes and farms were developed in the area. The railroad between San Francisco and San Jose built a train station at San Bruno in the 1860s. The railroad eventually became part of the Southern Pacific system, which ran both passenger and freight trains on the line. Today it is known as Caltrain.

A U.S. Post Office was first established at San Bruno in 1875. Postal services were discontinued for several months in both 1890 and 1891, then from 1893 to 1898. There has been a post office in San Bruno continuously since 1898. The present post office is located near the Tanforan Shopping Center.[30][31]

20th century

[edit]Real growth and development began after the 1906 earthquake and fire. The city's first public school was completed in late 1906. With the construction of Edgemont Elementary School in 1910, all classes were moved there and the original school building became a public facility named Green Hall. Another school, North Brae Elementary School, opened in 1912; among its earliest students was future actor Eddie "Rochester" Anderson. Paving of California's first state highway, El Camino Real, began in 1912 in front of San Bruno's Uncle Tom's Cabin; the highway is now designated as State Route 82. The adjoining San Francisco International Airport opened in early 1927 and included a Weather Bureau station, now operated by the National Weather Service. Charles Lindbergh was an early visitor to the airport, during his national tour following his successful transatlantic flight; his airplane (Spirit of St. Louis) became stuck in the mud.

On January 18, 1911, aviator Eugene Ely made naval aviation history when he took off from Tanforan Racetrack and made a successful landing on the armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania anchored in San Francisco Bay.[32] This marked the first successful shipboard aircraft landing.[33]

Following a campaign by the local newspaper, the San Bruno Herald, the community was incorporated in 1914, mainly so the streets could be paved. Green Hall became the first city hall. San Bruno grew rapidly, passing 1,500 residents by 1920 and 3,610 residents in 1930. Additional schools, including New Edgemont (later renamed Decima Allen) and Crystal Springs, were built during the 1940s.

In 1930, the El Camino Theater opened at the corner of El Camino Real and San Mateo Avenue. The popular theater, wired for sound, replaced the earlier Melody Theater, which had presented silent films. The El Camino showed double features, cartoons, short comedies, adventure serials, and newsreels during its history, including Saturday matinees and summer Wednesday matinees for children. Normally, films changed every week, but in 1958 Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments ran for two weeks to packed audiences. The theater closed in the early 1970s when a four-screen movie theater opened in the Tanforan shopping center. The El Camino Theater building was remodeled, but later demolished. The lot is now home to mixed-use apartment and retail space.[34] A larger, multi-screen complex was later built north of Tanforan, but it has been replaced by an even larger complex, Century at Tanforan, in the remodeled shopping center.[35]

In 1939, the War Department created the Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno as space was starting to run out for veterans to be buried at the Presidio of San Francisco. In 1942, after the start of World War II, the local racetrack became the Tanforan Assembly Center, a temporary detention site for Japanese Americans evicted from the West Coast under Executive Order 9066.[36]

Following World War II, there was continued growth and new subdivisions were built in Mills Park, Rollingwood, and Crestmoor. In 1947, the Bayshore Freeway (U.S. Route 101) was opened from South San Francisco to Redwood City and included an interchange at San Bruno.

Prior to 1950, San Bruno's high school students attended San Mateo High School (opened in 1902) and then Burlingame High School (opened in 1923), traveling to and from school on the streetcars that ran next to the Southern Pacific railroad. Finally, on September 11, 1950, Capuchino High School opened in San Bruno. After years of using Green Hall as a multi-purpose building, the city dedicated a library and city hall in 1954. That same year saw the dedication of the current central terminal at the airport, part of a major expansion program. A central fire station was later built next to the city hall; an additional station was built in Crestmoor.

Actress and businesswoman Suzanne Somers was born in San Bruno in 1946. She attended local schools and graduated from Capuchino High School in June 1964.

In 1953, San Bruno annexed the adjoining unincorporated community of Lomita Park, bounded by San Felipe Avenue, El Camino Real, San Juan Avenue, and the railroad tracks.[37] Until the annexation, Lomita Park had its own Southern Pacific train station and some community services.

Parkside Intermediate School was opened in 1954, followed by additional elementary schools: Rollingwood, Crestmoor, John Muir, and Carl Sandburg. A second intermediate school, Engvall, was built in Crestmoor Canyon, only to be closed, along with North Brae and Sandburg, when enrollment fell. These were all part of the San Bruno Park School District. Students in northwestern San Bruno were included in the Laguna Salada district. Highlands Christian School, a private school, is also located in San Bruno. Founded in 1966, Highlands Christian School is an interdenominational school, and offers preschool through college preparatory school instruction.

San Bruno considered new annexations in the mid-1950s that would have extended the city limits to the Pacific Ocean. The unincorporated communities west of San Bruno were against annexation, and collectively incorporated as the city of Pacifica in 1957.

On March 22, 1957, a magnitude 5.7 earthquake was centered in the area of the city.[38] It inflicted minor damage throughout the city.

Eitel-McCullough operated a large manufacturing plant in San Bruno for many years. William Eitel and Jack McCullogh formed the company in 1934. It specialized in the manufacture of power grid tubes.[39] Known as Eimac, the company also made vacuum tubes used in communication equipment, as well as other products for military and commercial applications.[40] Due to its work on broadcast transmission parts, Eimac operated an FM radio station, KSBR, which transmitted on 100.5 megahertz.[41] The station began operations in 1947 and, that same year, was one of only two in the nation to test Rangertone tape recorders. (The other station was WASH-FM in Washington, D.C.)[42] The recorders were based on the German Magnetophon.[43] In need of more space, the company moved to San Carlos in 1959.[44] Eimac's San Carlos plant was dedicated on April 16, 1959.[44] In 1965, Eimac merged with Varian Associates and became known as the Eimac Division. In 1995, Leonard Green & Partners purchased the entire Electron Devices Business from Varian and formed Communications & Power Industries.[45]

Crestmoor High School opened in September 1962, but was closed in June 1980 due to a decline in school enrollment. The city has a two-year community college, Skyline College.

A major landmark in San Bruno for many years was Tanforan Racetrack, which opened in 1899. Such famous racehorses as Seabiscuit and Citation raced there. Famed Hollywood director Frank Capra filmed scenes for two of his films, Broadway Bill and Riding High, at the racetrack. For six months in 1942, it served as one of the main Bay Area centers for those forced into Japanese American internment, processing about 8,000 Japanese before they were sent out to larger facilities in the desert of Utah and Manzanar in Owens Valley.[46] The track closed in 1964 and was about to be demolished when it was destroyed in a major fire on July 31, 1964.[47] The Shops at Tanforan mall was later built on the site; surrounding city streets were named for some of the racehorses who appeared at Tanforan.

The city was the site of the crash of Flying Tiger Line Flight 282 on December 23, 1964.

During the late 1960s, the I-280 (Junipero Serra Freeway), followed by I-380, was built through San Bruno. The San Bruno Planning Commission (then chaired by Peter Weinberger, brother of Caspar Weinberger) reviewed and approved plans for two major shopping centers, Bayhill (located on the old U.S. Navy property between San Bruno Avenue and Sneath Lane) and Tanforan. With final approval from the San Bruno City Council, construction proceeded on these major retail developments. Prior to these developments, most of the city's retail businesses were located on San Mateo Avenue and El Camino Real.

San Bruno is one of two cities in the Bay Area that manages its own cable TV and internet system.

The October 17, 1989, Loma Prieta earthquake (6.9 magnitude) caused some damage in the city. The U.S. Postal Service's Western Regional headquarters, which was then the tallest building in San Bruno, had to be demolished due to severe structural damage. The site was rebuilt as part of an expansion of The Gap clothing company world headquarters campus.[48][49] The building now houses the headquarters for Wal-Mart's online retail services,[50] Walmart.com, and is now the tallest building in the city.

21st century

[edit]The San Bruno BART station opened in 2003, when the transit system was extended to Millbrae and the San Francisco International Airport.

September 2010 explosion and fire

[edit]

On September 9, 2010, at about 6:15 p.m. PDT, a gas line ruptured leading to a fire that severely damaged a residential neighborhood. Eight people were killed, nearly 60 others were injured, 38 homes were destroyed and 123 additional homes were damaged.[51][52] The resulting fire "hot spots" were easily detected using meteorological satellite images.[53]

The explosion, which took place two miles (3.2 km) west of San Francisco International Airport (37°37′23″N 122°26′31″W / 37.623°N 122.442°W), was initially thought to have been a plane crash, but the FAA and airport officials confirmed no downed aircraft was reported.[54][55]

During the days prior to the explosion, some residents reported a strong smell of natural gas in the area.[56][57]

On September 10, a team from the National Transportation Safety Board began an investigation into the cause of the explosion.[58]

On September 13, PG&E agreed to set aside a $100 million fund to the victims of the explosion. This does not preclude residents from taking any further action against PG&E. Parts of the exploded material were taken to Washington, D.C., a couple of days after the explosion for examination.[59]

YouTube headquarters

[edit]In 2007, YouTube had moved its headquarters from San Mateo, California to San Bruno, on Cherry Avenue next to Interstate 380.[60] The main building was initially built for Gap Inc. in 1997.[61] It had been designed in 1994, has a green roof, and was built with energy efficient ventilation systems.[62] Across more than six properties, YouTube has over 2,000 employees working in the city, and is San Bruno's largest employer.[63] On April 3, 2018, a shooting took place at the headquarters complex, leaving four wounded and the female shooter dead.[64]

Former Naval Facility San Bruno

[edit]

During World War II the United States Navy established a base on what was a dairy opened by Richard Sneath.[65] There it operated a Classification Center and a Naval Advance Base Personnel Depot.[66] After the war it continued operation,[67] and became host to the consolidated Western Division of Naval Facilities, supporting the multiple navy bases that were operating in the greater San Francisco Bay Area.[68] Due to the 1993 BRAC and its closure of neighboring bases although recommended for realignment, the Navy decided to close the facility, carrying through with its decision in October 1994.[69]

The federal government retained part of the former Naval Facility. The Pacific Region (San Francisco) facility of the National Archives and Records Administration was established.[70] One of the buildings became a Navy and Marine Corps Reserve Center, which hosts the Headquarters Company of the 23rd Marine Regiment, amongst other units.[71][72] The rest of the facility was sold to a private developer who has since built multi-story apartment buildings on the former base.[73] The 20-acre (81,000 m2) area of the former U.S. Navy complex is bounded by San Bruno Avenue, El Camino Real, Sneath Lane, and I-280.

Economy

[edit]Top employers

[edit]According to San Bruno's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report[74] and the San Mateo Daily Journal[75] the top employers in the city were:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Walmart Global eCommerce | 3,200 |

| 2 | YouTube | 2,380 |

| 3 | Skyline College | 680 |

| 4 | Artichoke Joe's | 389 |

| 5 | Target | 255 |

| 6 | San Bruno Park School District | 235 |

| 6 | City of San Bruno | 235 |

| 8 | Lucky Supermarkets | 199 |

| 9 | Lowe's | 180 |

| 10 | JC Penney | 164 |

Transportation

[edit]Roads

[edit]

Interstate 280, running concurrent with California State Route 1, passes through San Bruno, and Interstate 380, which is entirely located within the city, flanks the northern part of San Bruno and connects with U.S. Route 101. The town is bisected by California State Route 82.

Public transit

[edit]

SamTrans operates bus public transport within San Mateo County, with several routes through San Bruno. Commuter rail to and from San Bruno is served by Caltrain, and Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) has its Red and Yellow lines serve San Bruno.[76]

Both the San Bruno Caltrain and BART stations are very close to the Shops at Tanforan; the BART station is adjacent to both the shopping mall and an intermodal transfer station for samTrans, serving its primary line, ECR, which operates between Daly City and Palo Alto along El Camino Real. The Caltrain station is approximately 1 km (0.62 mi) further south along Huntington Avenue.

Air transport

[edit]San Bruno is adjacent to San Francisco International Airport, which can be accessed using BART or US 101. However, the other major San Francisco Bay Area airports (Oakland and San Jose) are accessible from San Bruno via BART for the former and Caltrain plus VTA services for the latter.

Notable people

[edit]- Wally Bunker, baseball player

- Emma Chamberlain, Internet personality

- Neal Dahlen, football administrator

- Luana DeVol, soprano

- Keith Hernandez, baseball player

- Nelson Holderman, WW1 Medal of Honor recipient

- Ky Hollenbeck, kickboxer

- Ron "Pigpen" McKernan, musician

- The Mummies, garage punk band

- Ruggiero Ricci, violinist

- Suzanne Somers, actress

- Romaine Welds, Jamaican-American man who visited every country in the world, lives in San Bruno[77]

Sister cities

[edit]- Narita, Chiba Prefecture, Japan[78]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Whiting, Sam (February 8, 2004). "The Heart of San Bruno / Hidden within an unusually shaped housing tract is Cupid Row". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

Livengood, Carolyn (January 21, 2011). "Carolyn Livengood: San Bruno honors Glenview residents". Mercury News. San Jose, California. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

Clifford, Jim (February 8, 2016). "San Bruno has a heart every day". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved February 9, 2016. - ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "San Bruno - Government". City of San Bruno. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ a b "City Council". City of San Bruno. Archived from the original on September 20, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "San Bruno". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- ^ "San Bruno (city) QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?ca7769; http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/clilcd.pl?ca23234

- ^ "General Climate Summary Tables - SAN FRANCISCO INTL AP, CALIFORNIA". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - San Bruno city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "Bay Area Census". www.bayareacensus.ca.gov.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "San Bruno city, California - Fact Sheet - American FactFinder". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on February 11, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

- ^ Schuessler, Anna (November 8, 2017). "Medina's the mayor". The Daily Journal. San Bruno. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

Walsh, Austin (December 18, 2017). "Dedicated councilman takes his leave". The Daily Journal. San Bruno. Retrieved April 22, 2018. - ^ Welcome to the City of San Bruno, California Archived January 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Sanbruno.ca.gov. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Melvin, Joshua (August 15, 2016). "7 hopefuls vie for spot on San Bruno City Council". East Bay Times. Bay Area News Group. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

Melvi, Joshua (May 9, 2012). "Longtime San Bruno Mayor Bob Marshall dies". The Mercury News. Bay Area News Group. Retrieved May 9, 2018. - ^ Schuessler, Anna (November 8, 2017). "Medina's the mayor". San Mateo Daily Journal. San Bruno. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

... to the Peninsula's only independently elected mayoral position ...

- ^ "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ "California's 15th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ "San Bruno City Park". City of San Bruno. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ "Junipero Serra Park". County of San Mateo. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b John Horgan (February 19, 2013). "John Horgan: San Bruno's lack of kids is taking its toll". San Mateo County Times. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ Darold Fredricks (July 23, 2012). "San Bruno early development". San Mateo Daily Journal. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ Waterman L. Ormsby, Lyle H. Wright, Josephine M. Bynum, The Butterfield Overland Mail: Only Through Passenger on the First Westbound Stage. Henry E. Huntington Library and Art Gallery, 2007. pp.92-93.

- ^ Darold Fredricks (2003). San Bruno. San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 4, 11. ISBN 978-0-7385-2859-5.

- ^ David L. Durham (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic & Modern Names of the State. Word Dancer Press. p. 690. ISBN 978-1-884995-14-9.

- ^ "City History, from". www.sanbruno.ca.gov. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Eugene Ely's Flight to USS Pennsylvania, 18 January 1911 – Narrative and Special Image Selection". History.navy.mil. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ "Eugene B. Ely, Aviator, (1886-1911)". History.navy.mil. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ Bryan Krefft. "El Camino Theatre". Cinema Treasures, LLC. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ^ Century at Tanforan and XD Showtimes & Tickets - 94066 Movie Theaters. Movies.eventful.com. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Kawahara, Lewis. "Tanforan" Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ^ People v. City of San Bruno (1954), Text.

- ^ Geological Survey Professional Paper. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1982. p. 4.

- ^ "Technology and Entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ none (1940). "Exhibitors at the Radio Engineering Show". Proceedings of the IRE. 28 (5): vi. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1940.229071.

- ^ http://jeff560.tripod.com/1948fm.html; http://bostonradio.org/fm-1950.html

- ^ David Morton (2000). Off the Record: The Technology and Culture of Sound Recording in America. Rutgers University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-8135-2747-5.

- ^ "A Biography of Richard Ranger and History of the Rangertone Corp". Archived from the original on November 25, 2010.

- ^ a b "Eitel-McCullough, Inc. building in San Carlos, 1959". Content.cdlib.org. March 23, 2006. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ (in German) Eimac manufacturer in USA, Tube manufacturer from United Sta. Radiomuseum.org. Retrieved on July 21, 2013.

- ^ Gary Y. Okihiro (June 11, 2013). Encyclopedia of Japanese American Internment. ABC-CLIO. pp. 226–228. ISBN 978-0-313-39916-9.

- ^ Alan Michelson (2005). "Tanforan Race Track, San Bruno, CA". Pacific Coast Architecture Database. University of Washington. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ "Gap Office Building, 901 Cherry Street". Center for the Built Environment. The Regents of the University of California. Archived from the original on December 14, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ "The Gap, Inc". CalRecycle. State of California. April 15, 2002. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Dineen, J. K. (May 2, 2010). "Walmart.com bags new headquarters". San Francisco Business Times. American City Business Journals. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ^ Sandra Gonzales; Mike Rosenberg; Jesse Dungan; Diana Samuels (September 9, 2010). "San Bruno explosion and fire destroys dozens of homes; one dead, many injured". Mercury News. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Trevor Hunnicutt (September 9, 2010). "1 death confirmed in fire south of San Francisco". Yahoo! News. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Deadly natural gas explosion and fire in San Bruno, California". CIMSS Satellite Blog. September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Homes ablaze after explosion near San Francisco". MSNBC. September 9, 2010.

- ^ Lagos, Marisa; Fagan, Kevin; Cabanatuan, Michael; Berton, Justin (September 14, 2010). "San Bruno fire levels neighborhood - gas explosion". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam; Wollan, Malia (September 10, 2010). "Inquiry Sifting Cause of Blast in the Bay Area". The New York Times.

- ^ "Natural gas explosion rocks San Bruno; 4 dead". ABC7 News. September 10, 2010. Archived from the original on September 11, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- ^ Lowy, Joan (September 10, 2010). "NTSB to investigate explosion, fire in Calif". San Francisco Chronicle.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "PG&E sets aside $100M fund for Calif Blast Victims". Associated Press. September 13, 2010.

- ^ Donato-Weinstein, Nathan (December 13, 2013). "YouTube expands San Bruno space by 33 percent, room for 375 workers". Silicon Valley Business Journal. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Nakashima, Ryan; Thanawala, Sudhin (April 3, 2018). "Law enforcement officials ID YouTube shooter as Nasim Aghdam of Southern California". KTVU. Oakland. Associated Press. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Steven L. Cantor; Steven Peck (2008). Green Roofs in Sustainable Landscape Design. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-393-73168-2.

Corky Binggeli (January 21, 2003). Building Systems for Interior Designers. John Wiley & Sons. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-471-26651-8. - ^ Lee, Wendy (April 3, 2018). "YouTube is San Bruno's largest employer". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Re, Gregg (April 3, 2018). "YouTube shooter ID'd as woman with apparent vendetta against company". Fox News. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- ^ Rusmore, Jean; Frances Spangle; Betsy Crowder; Sue LaTourrette (2005). Peninsula trails: hiking & biking trails on the San Francisco Peninsula. Wilderness Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-89997-366-1.

- ^ "Major Navy and Marine Corps Installations During World War II". The California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. February 20, 2009. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "The San Bruno Historical Photo Gallery". History. City of San Bruno. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "History". NAVFAC Southwest. U.S. Navy. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "1993 Commission Recommendations". Base Closures and Realignments. Department of Defense. March 31, 1996. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "Pacific Region (San Francisco)". Pacific Region. The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "Headquarters Company, 23rd Marine Regiment". Marine Forces Reserve. United States Marine Corps. October 28, 2004. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "23rd Marine Regiment". GlobalSecurity.org. John Pike. April 26, 2005. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ Worth, Katie (May 13, 2009). "The Crossing in San Bruno wins mixed reviews". Local. San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved May 29, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "City of San Bruno CAFR". Archived from the original on May 10, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ staff, Austin Walsh Daily Journal (February 14, 2018). "San Bruno's tax revenue still growing". San Mateo Daily Journal.

- ^ "Public Transit". City of San Bruno. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ Clay, Rebecca A. (May 2, 2023). "The SFO worker who has traveled to every country in the world, including North Korea". SF Gate. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ "Consolidation of Local Governments in Japan and Effects on Sister City Relationships Archived 2007-10-19 at the Wayback Machine", Consulate General of Japan, San Francisco

External links

[edit]- San Bruno, California

- 1849 establishments in California

- 1914 establishments in California

- Cities in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Butterfield Overland Mail in California

- Cities in San Mateo County, California

- Incorporated cities and towns in California

- Populated places established in 1849

- Populated places established in 1914