Downtown Eastside

Downtown Eastside | |

|---|---|

Neighbourhood | |

The Downtown Eastside and Woodward's site at dusk, from Harbour Centre in summer 2018 | |

| Nicknames: DTES, Skid Row | |

| Coordinates: 49°16′53″N 123°05′59″W / 49.28139°N 123.09972°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| City | Vancouver |

| Government | |

| • MP | Jenny Kwan |

| • MLA | Joan Phillip |

| Population (2011) | |

• Total | 18,477 for the greater DTES area |

• Estimate (2009) | 6,000 – 8,000 for the DTES |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| Postal code | V6A |

| Area codes | 604, 778, 236, 672 |

The Downtown Eastside (DTES) is a neighbourhood in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. One of the city's oldest neighbourhoods, the DTES is the site of a complex set of social issues, including disproportionately high levels of drug use, homelessness, poverty, crime, mental illness and sex work. It is also known for its strong community resilience, history of social activism, and artistic contributions.

Around the beginning of the 20th century, the DTES was Vancouver's political, cultural and retail centre. Over several decades, the city centre gradually shifted westwards, and the DTES became a poor neighbourhood,[1] although relatively stable. In the 1980s, the area began a rapid decline due to several factors, including an influx of hard drugs, policies that pushed sex work and drug-related activity out of nearby areas, and the cessation of federal funding for social housing. By 1997, an epidemic of HIV infection and drug overdoses in the DTES led to the declaration of a public health emergency. As of 2018, critical issues include opioid overdoses, especially those involving the drug fentanyl; decrepit and squalid housing; a shortage of low-cost rental housing; and mental illness, which often co-occurs with addiction.

The population of the DTES is estimated to be around 7,000 people. Compared to the city, the DTES has a higher proportion of males and adults who live alone. It also has significantly more Indigenous Canadians, disproportionately affected by the neighbourhood's social problems.[2][3][4] The neighbourhood has a history of attracting individuals with mental health and addiction issues, many of whom are drawn to its drug market and low-barrier services. Residents experience Canada's highest rate of death from encounters with police,[5] and there is mutual mistrust between police and many homeless residents.

Since Vancouver's real-estate boom began in the early 21st century, the area has been increasingly experiencing gentrification. Some see gentrification as a force for revitalization, while others believe it has led to higher displacement and homelessness. Numerous efforts have been made to improve the DTES at an estimated cost of over $1.4 billion as of 2009. Services in the greater DTES area are estimated to cost $360 million per year.[6] Commentators from across the political spectrum have said that little progress has been made in resolving the issues of the neighbourhood as a whole, although there are individual success stories. Proposals for addressing the issues of the area include increasing investment in social housing, increasing capacity for treating people with addictions and mental illness, making services more evenly distributed across the city and region instead of concentrated in the DTES, and improving coordination of services. However, little agreement exists between the municipal, provincial and federal governments regarding long-term plans for the area.

Geography

[edit]

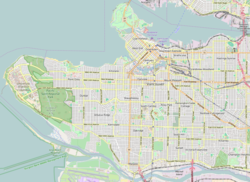

The term "Downtown Eastside" is most often used to refer to an area 10[7] to 50[8] blocks in size, a few blocks east of the city's Downtown central business district. The neighbourhood is centred around the intersection of Main Street and Hastings Street, where residents have gathered for over a hundred years to connect.[9] This intersection is also the home of the Carnegie Community Centre. The area around Hastings and Main is where the neighbourhood's social issues are most visible,[10] described in the Vancouver Sun in 2006 as "four blocks of hell."[11]

Some indications of the borders of the DTES, which shift and are poorly defined,[12] are as follows:

- A 2016 analysis of crime in the DTES by The Georgia Straight focused on an area that consisted of a six-block length of Hastings and Cordova Streets, between Cambie Street and Jackson Avenue.[13]

- The City of Vancouver describes a "Community-based Development Area", where places important to low-income residents are concentrated. This area includes Hastings Street from Abbott Street to Heatley Avenue, and the blocks surrounding Oppenheimer Park.[14]

- By some definitions, the DTES extends along Main Street to beyond Terminal Avenue, and the DTES also includes a strip of land adjacent to Vancouver's port.[12]

For some community planning and statistical purposes, the City of Vancouver uses the term "Downtown Eastside" to refer to a much larger area with considerable social and economic diversity, including Chinatown, Gastown, Strathcona, the Victory Square area, and the light industrial area to the north. This area, referred to in this article as the greater DTES area, is bordered by Richards Street to the west, Clark Drive to the east, Waterfront Road and Water Street to the north and various streets to the south including Malkin Avenue and Prior Street.[15] The greater DTES area includes some popular tourist areas and nearly 20% of Vancouver's heritage buildings. [16]

Strathcona in the 1890s included the entire DTES. By 1994 Strathcona's northern boundary was generally considered to be the alley between East Pender and East Hastings streets,[17] though some place it at Railway Street, including DTES east of Gore Avenue.[18]

History

[edit]

The DTES forms part of the traditional territories of the Squamish, Tsleil-Waututh, and Musqueam First Nations.[19] European settlement of the area began in the mid-19th century, and most early buildings were destroyed in the Great Vancouver Fire of 1886.[1] Residents rebuilt their town at the edge of Burrard Inlet, between Cambie and Carrall streets, a townsite that now forms Gastown and part of the DTES.[1] At the turn of the century, the DTES was the heart of the city, containing city hall, the courthouse, banks, the main shopping district, and the Carnegie Library.[1] Travellers connecting between Pacific steamships and the western terminus of the Canadian Pacific Railway used its hundreds of hotels and rooming houses.[20] Large Japanese and Chinese immigrant communities settled in Japantown, which lies within the DTES, and in nearby Chinatown, respectively.[21]

During the Depression, hundreds of men arrived in Vancouver searching for work. Most of them later returned to their hometowns, except workers who had been injured or those who were sick or elderly.[1] These men remained in the DTES area – at the time known as Skid Road – which became a non-judgemental, affordable place to live as the main downtown area of Vancouver began to shift westward. Among them, drinking was a common pastime.[1][22] In addition to being a central cultural and entertainment district, Hastings Street was also a centre for beer parlours and brothels.[23]

In 1942, the neighbourhood lost its entire ethnic Japanese population, estimated at 8,000 to 10,000, due to the Canadian government's internment of these people. After the war, most did not return to the once-thriving Japantown community.[24]

In the 1950s, the city centre continued its shift westward after the interurban rail line closed; its main depot was at Carrall and Hastings.[25] Theatres and shops moved towards Granville and Robson streets.[26] As tourist traffic declined, the neighbourhood's hotels became run-down and were gradually converted to single room occupancy (SRO) housing, a use which persists to this day.[1] By 1965, the area was known for prostitution and for having a relatively high proportion of poor, single men, many of whom were alcoholics, disabled, or pensioners.[1]

1980s

[edit]

When we deinstitutionalized, we promised [mentally ill] people that we would put them into the community and give them the support they needed. But we lied. I think it's one of the worst things we ever did.

— Senator Larry Campbell, former mayor of Vancouver, [27]

In the early 1980s, the DTES was an edgy but still relatively calm place to live. The neighbourhood began a marked shift before Expo 86, when an estimated 800 to 1,000 tenants were evicted from DTES residential hotels to make room for tourists.[28] With the increased tourist traffic of Expo 86, dealers introduced an influx of high-purity cocaine and heroin.[29] In efforts to clean up other areas of the city, police cracked down on the cocaine market and street prostitution, but these activities resurfaced in the DTES.[29][30] Within the DTES, police officers gave up on arresting the huge numbers of individual drug users, and chose to focus their efforts on dealers instead.[31]

Meanwhile, the provincial government adopted a policy of de-institutionalization of the mentally ill, leading to the mass discharge of Riverview Hospital's patients, with the promise that they would be integrated into the community.[27] Between 1985 and 1999, the number of patient-days of care provided by B.C. psychiatric hospitals declined by nearly 65%.[27] Many of the de-institutionalized mentally ill moved to the DTES, attracted by the accepting culture and low-cost housing, but they floundered without adequate treatment and support and soon became addicted to the neighbourhood's readily available drugs.[32][33]

Between 1980 and 2002, more than 60 women went missing from the DTES, most of them sex workers. A large number are missing and murdered Indigenous women.[34] Robert Pickton, who had a farm east of the city where he held "raves", was charged with the murders of 26 of these women and convicted on six counts in 2007. He claimed to have murdered 49 women.[35] As of 2009, an estimated 39 women were still missing from the Downtown Eastside.[36]

1990s to present

[edit]

On its core blocks, dozens of people are shuffling or staggering, flinching with cocaine tics, scratching scabs. Except for the young women dressed to lure customers for sex, many are in dirt-streaked clothing that hangs from their emaciated frames. Drugs and cash are openly exchanged. The alleys are worse.

— The New York Times, 2011, [37]

In the 1990s, the situation in the DTES deteriorated further on several fronts. Woodward's, an anchor store in the 100-block of West Hastings street, closed in 1993 with devastating effect on the formerly bustling retail district.[38] Meanwhile, a crisis in housing and homelessness was emerging.

Between 1970 and the late 1990s, the supply of low-income housing shrank in both the DTES and in other parts of the city, partly because of the conversion of buildings into more expensive condominiums or hotels.[27] In 1993, the federal government stopped funding social housing, and the rate of building social housing in B.C. dropped by two-thirds despite rising demand for it.[27] By 1995, reports had begun to emerge of homeless people sleeping in parks, alleyways, and abandoned buildings.[27] Cuts to the provincial welfare program in 2002 caused further hardship for the poor and homeless.[27] Citywide, homeless people climbed from 630 in 2002 to 1,300 in 2005.[27]

Without a viable retail economy, a drug economy proliferated, with an accompanying increase in crime,[26] while police presence decreased.[39] Crack cocaine arrived in Vancouver in 1995,[27] and crystal methamphetamine started to appear in the DTES in 2003.[31] In 1997 the local health authority declared a public health emergency in the DTES: Rates of HIV infection, spread by needle-sharing amongst drug users, were worse than anywhere in the world outside Sub-Saharan Africa, and more than 1000 people had died of drug overdoses.[40][41] Efforts to reduce drug-related deaths in the DTES included the opening of a needle exchange in 1989,[42] the opening of North America's first legal safe injection site in 2003, and treatment with anti-retroviral drugs for HIV.[43] A shift among users from injected cocaine to crack cocaine use may have also slowed the spread of disease.[44] Rates of HIV infection dropped from 8.1 cases per 100 person-years in 1997 to 0.37 cases per 100 person-years by 2011.[45]

In the 21st century, considerable investment was made in DTES services and infrastructure, including the Woodward's Building redevelopment and the acquisition of 23 SRO hotels by the provincial government for conversion to social housing.[46] In 2009, The Globe and Mail estimated that governments and the private sector had spent more than $1.4 billion since 2000 on projects aimed at resolving the area's many problems.[47]

Opinions vary on whether the area has improved: A 2014 article in the National Post said, "For all the money and attention here, there is little success at either getting the area's shattered populace back on their feet or cleaning up the neighbourhood into something resembling a healthy community."[48] Former NDP premier Mike Harcourt described the current reality of the neighbourhood as "100-per-cent failure."[49] Also in 2014, B.C. housing minister Rich Coleman claimed "I'll go down for a walk in the Downtown Eastside, night time or day time, and it's dramatically different than it was. It's incredibly better than it was five, six years ago."[6]

Demographics

[edit]

There are no official population figures for the DTES. Estimates have ranged from 6,000[47] to 8,000;[23] the geographic boundaries associated with these figures were not provided.

Official figures are available for the greater DTES area, which was home to an estimated 18,477 people in 2011.[50] In comparison to the city of Vancouver overall, the greater DTES had a higher proportion of males (60% vs. 50%), more seniors (22% vs 13%), fewer children and youth (10% vs 18%), slightly fewer immigrants, and more Indigenous Canadians (10% vs. 2%).[51]

A 2009 demographic profile by The Globe and Mail focused on an area of just over 30 city blocks in and around the DTES: It indicated that 14% of the residents were of Indigenous descent.[52] The average household size was 1.3 residents; 82% of the population lived alone. Children and teenagers made up 7% of the people, compared to 25% of Canada overall.[52]

A population that is frequently studied is tenants of single-room occupancy (SRO) hotels in the greater DTES area. According to a 2013 survey, this population is 77% male, with a median age of 44. Indigenous people make up 28% of the population, and Europeans 59%.[53]

Migration patterns

[edit]The DTES has a history of attracting migrants with mental health and addiction issues across B.C. and Canada, with many drawn by its drug market, affordable housing, and services.[54][55][56][57] Between 1991 and 2007, the DTES population increased by 140%.[55]

A 2016 study found that 52% of those DTES residents who experience chronic homelessness and serious mental health issues had migrated from outside Vancouver in the previous 10 years. This proportion of the population has tripled in the last decade.[58] The same study found that once migrants had settled in the DTES, their conditions worsened.[58] A 2013 study of tenants of DTES SROs found that while 93% of those surveyed were born in Canada, only 13% were born in Vancouver.[59] Vancouver Coastal Health estimates that half of the population that uses its health services in the DTES are long-term residents and that there is a population turnover of 15 to 20% each year.[58]

Culture

[edit]

Although many outsiders fear the DTES,[60] its residents take pride in their neighbourhood and describe it as having multiple positive assets.[21] DTES residents say the area has a strong sense of community and cultural heritage.[61] They describe their neighbours as accepting and empathizing with people with addictions and health issues.[61] According to the city government, Hastings Street is valued by SRO residents as "a place to meet friends, get support, access services and feel like they belong."[62]

The area has had a robust tradition of advocacy for its marginalized residents since at least the 1970s when the Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA) was formed.[63] Over the years, the DTES community has consistently resisted many attempts to "clean up" the neighbourhood by dispersing its close-knit residents.[64] Successful resident-led initiatives to improve conditions in the DTES include the transformation of the then-closed Carnegie Library into a community centre in 1980,[63] the opening of an unlicensed supervised injection site in 2003, which led to the founding of Insite;[65] improvements to Oppenheimer Park,[66] and the creation of CRAB Park.

In 2010, the V6A postal area, which includes most of the DTES, had the second-highest concentration of artists in the city.[67] Artists made up 4.4% of the labour force, compared to 2.3% in the city as a whole.[67] The Downtown Eastside Artists' Collective was formed by Trey Helten, manager of the Overdose Prevention Society.[68] The greater DTES area is the location of several art galleries, artist-run centres and studios.[69] Prominent local artists include poet Henry Doyle,[70] artist Marcel Mousseau,[71] and poet Bud Osborn.[72]

Notable annual events include the Downtown Eastside Heart of the City Festival,[73] which showcases the art, culture, and history of the neighbourhood, and the Powell Street Festival in Oppenheimer Park, which celebrates Japanese-Canadian arts and culture. The Smilin' Buddha Cabaret operated at 109 East Hastings Street from 1952 to the late 1980s as a symbol of "cultural vitality," reflecting shifts in the neighbourhood itself.[74] City Opera of Vancouver, the Dancing on the Edge Festival, and other artists regularly perform in DTES venues such as the Carnegie Centre, the Firehall Arts Centre, and the Goldcorp Centre for the Arts at the Woodward's site. The musical composition "100 Block Rock," featuring 11 tracks, was released in 2020.[75] In 2010, Sam Sullivan, former mayor of Vancouver, said that in the DTES, "Behind the visible people who have a lot of troubles, there's a community. Some very intelligent people say this is the city's cultural heart."[76]

Current issues

[edit]Addiction and mental illness

[edit]The DTES population suffers very high rates of mental illness and addiction. In 2007, Vancouver Coastal Health estimated that 2,100 DTES residents "exhibit behaviour that is outside the norm" and require more support in the areas of health and addiction services.[77] According to the Vancouver Police Department (VPD) in 2008, up to 500 of these individuals were "chronically mentally ill with disabling addictions, extreme behaviours, no permanent housing and regular police contact."[78] As of 2009, the DTES was home to an estimated 1,800 to 3,600 individuals who were considered to be at "extremely high health risk" due to severe addiction or mental illness, equivalent to 60% of the population in this category for the 1 million people in the Vancouver Coastal Health region.[79]

A 2013 study of SRO tenants in the greater DTES found that 95.2% had some form of substance dependence, and 74.4% had a mental illness, including 47.4% with psychosis.[53] Only one-third of individuals with psychosis received treatment, and among those with concurrent addiction, the proportion receiving treatment was even lower.[53] A 2016 study of the 323 most chronic offenders in the DTES found that 99% had at least one mental disorder, and more than 80% also had substance abuse issues.[80] Between 60% and 70% of mentally ill patients treated at St. Paul's Hospital, the hospital closest to the DTES, are estimated to have multiple addictions.[81] Possible explanations for the high level of co-occurrence between addiction and mental illness in the DTES include the vulnerability of the mentally ill to drug dealers and a recent rise in crystal methamphetamine use, which can cause permanent psychosis.[31][82]

Substance use

[edit]A 2010 BBC article described the DTES as "home to one of the worst drug problems in North America."[83] In 2011, crack cocaine was the most commonly used illicit hard drug in Vancouver, followed by injected prescription opioids (such as fentanyl and OxyContin), heroin, crystal methamphetamine (usually injected rather than smoked), and cocaine (also usually injected).[45] Alcoholism, especially when it involves the use of highly toxic isopropyl alcohol, is a significant source of harm to residents of the DTES.[56]

In 2016, a board member of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users said that in the previous year, Vancouver's supply of heroin had virtually disappeared and been replaced by fentanyl, which is cheaper and more potent.[84] At the end of 2014, the DTES saw a dramatic rise in fentanyl overdoses. In 2016 the surge in drug overdose deaths led to the declaration of a public health emergency across the province.[85]

In a 2008 survey of SRO residents in the greater DTES, 32% self-reported as being addicted to drugs, 20% were addicted to alcohol, 52% smoked cigarettes regularly, and 51% smoked marijuana.[86] In 2003, the DTES was home to an estimated 4,700 injection drug users.[87] Most live in unstable housing or are homeless,[87] and approximately 20% are sex workers.[45] In 2006, DTES residents incurred half of the deaths from illegal drug overdoses in the entire province.[88] Between 1996 and 2011, there have been large fluctuations in drug usage, with the most recent trend being an overall decline in illicit drug use between 2007 and 2011.[45] However, between 2010 and 2014, hospitalizations related to addictions increased by 89% at St. Paul's Hospital.[41]

According to a 2008 survey of greater DTES area SROs, tenants who used drugs estimated the cost of their habits at $30 per day, on average.[86] Some spend hundreds of dollars per day on drugs.[89][90] Police attribute much of the property crime in Vancouver to chronic repeat offenders who steal to support their drug habits.[89]

Mental illness

[edit]The VPD reported in 2008 that in its district, which includes the Downtown Eastside, mental health was a factor in 42% of all incidents in which police were involved.[91] The police department says its officers are often forced to act as front-line mental health workers due to lacking more appropriate support for this population.[92]

In 2013, the city and police department reported that in the previous three years, there had been a 43% increase in people with severe mental illness or addiction in the emergency department of St. Paul's Hospital. In Vancouver, apprehensions under the Mental Health Act rose by 16% between 2010 and 2012, and there was also an increase in the number of violent incidents involving mentally ill people.[93] Mayor Gregor Robertson described the mental health crisis as "on par with, if not more serious than" the DTES HIV / AIDS epidemic that had led to a declaration of a public health emergency in 1997.[93]

Overdose crisis

[edit]The overdose deaths in BC between 2003 and 2018 are up over 725%, and overdose deaths of minors 10–18 years old are up 260% in 10 years. Fraser and Vancouver Coastal Health Authority have had the highest number of illicit drug toxicity deaths (188 and 164 deaths, respectively) in 2019, making up 65% of all such deaths during this period. 2019: Vancouver Coastal Health Authority has the highest rate of illicit drug toxicity deaths (27 deaths per 100,000 individuals).[94]

In a report presented to the City Council of Vancouver by Mayor Kennedy Stewart on 20 December 2018 regarding the opioid crisis, he stated:[95]

As of December 16, 2018, an estimated 353 overdose deaths have occurred in Vancouver in 2018, which is almost on par with the 369 overdose deaths in 2017, despite the extensive harm reduction investments in Vancouver. Vancouver continues to have the highest death rates per capita in BC, with 58 deaths per 100,000 people this year. Vancouver Fire and Rescue Services are responding to 103 overdose-related emergency calls per week, slightly down from the 2017 average of 119 calls per week. The decreased rate in overdose deaths and calls could be attributed to the increase in overdose prevention and response interventions across Vancouver, emphasizing the Downtown Eastside. Regardless, Vancouver continues to be the city most impacted by the overdose crisis in Canada. From January to June 2018, BC had 754 opioid-related deaths – the country's highest. Vancouver also has more overdose deaths per capita than all of BC, with 30 deaths per 100,000 people between January and June 2018.

— Kennedy Stewart

Statistics indicate that illicit drug toxicity deaths have increased in BC, with 1,547 and 981 deaths in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Between January and September 2020, BC has seen the number of overdose deaths jump to 1,202, with a record high of 183 illicit drug-related deaths reported in June of this year. The Vancouver Coastal Health jurisdiction has seen 37 deaths per 100,000 people between January and October 2020.[96]

Sex work

[edit]In my 12 years as a physician in the DTES, I never met a female patient who had not been sexually abused as a child or adolescent, nor a male who had not suffered some form of severe trauma... Addictions are attempts to escape the pain.

— Gabor Maté, [57]

Vancouver has an estimated 1,000 street-based sex workers.[97] According to the police, most of them work in the DTES.[98] They call the neighbourhood and contiguous industrial areas near Vancouver's port these "outdoor workers" (previously referred to using the more stigmatizing language including "low track" workers),[99] where they typically earn $5 to $20 for a "date".[100] Most are survival sex workers who use sex work to support their substance use;[101] up to two-thirds say they have been physically or sexually assaulted while working.[100] Sex workers, particularly women with children, find it difficult to find housing that they can afford, and often have difficulty leaving the industry because of criminal records or addictions that make it harder to find jobs.[100]

Although Indigenous Canadians makeup only 2% of Vancouver's population, approximately 40% of Vancouver's street-based sex workers are Indigenous.[102] In one 2005 study, 52% of the sex workers surveyed in Vancouver were Indigenous, 96% reported having been sexually abused in childhood, and 81% reported childhood physical abuse. Some researchers and Indigenous advocacy groups have attributed the over-representation of Indigenous people in Vancouver's sex trade to transgenerational trauma, linking it to Canada's colonial history and in particular, to the cultural and individual damage caused by the residential schools, which previous generations of indigenous Canadians were forced to attend.[103]

Displacement

[edit]After the displacements that occurred on Dupont and Davie Street, Vancouver's outdoor sex workers were pushed to the streets of the Downtown Eastside. Here they are facing more violence than ever before. Neighbourhood harassment, policing, and developmental changes contribute to these conditions. Throughout all of the areas where sex work has been present, the city has been critiqued for backing up property owners to harass workers collectively.[104] In the Downtown Eastside, these behaviours have continued to persist. A study published in 2017 containing interviews with thirty-three sex workers addressed concerns with changes in construction, surveillance, and security measures that have pushed workers into isolated areas where they are at greater risk of harm. The growth of new businesses in the area has also required workers to develop good relations to prevent frequent police calls.[105] These conditions have also forced workers to rush or forgo screening and negotiation processes that increase the risk of bad dates and STI contractions. This disproportionately impacted the safety of oppressed communities such as indigenous, substance-dependent and transgender workers who are often restricted to this area.[106] Over the years, this has also contributed to the many missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) cases, including those involved in the mass killings by serial killer Robert Pickton.[107]

Crime and public disorder

[edit]

Reported crime rates in the DTES are higher than in the rest of the city, with most crimes being assaults, robberies, or public intoxication.[108] Although it is home to 3% of Vancouver's population, the DTES was the location of 16% of the city's reported sexual assaults in 2012.[102] In 2008, it was the location of 34.5% of all reported serious assaults and 22.6% of all robberies in the city.[109]

These figures may be an underestimate, as marginalized populations such as DTES residents tend to be less likely to report crime.[102] Many residents are survivors of the Canadian Indian residential school system or experience transgenerational trauma as a result of Residential Schools, and are further traumatized by excessive policing.[110]

The figures do not indicate how many of the reported crimes were committed by DTES residents; some residents and business owners believe that visitors from other neighbourhoods are responsible for a significant proportion of serious crimes.[13] According to police, DTES women say that what they fear most are "predatory drug dealers who conduct their business with violence, torture, and terror."[111]

In addition to reported crime, the DTES has the highly visible street disorder, which The New York Times described as "a shock even to someone familiar with the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the 1980s or the Tenderloin in San Francisco."[37] Some government social workers have refused to enter certain SROs out of concern for their safety, despite being mandated to monitor children who live there.[112] Tourists are often encouraged to avoid the DTES,.[113] However, they are seldom victims of crime.[114] High crime rates and difficulties in obtaining affordable property insurance deter legitimate businesses from opening or staying in the area, resulting in many vacant storefronts.[115][116]

Poverty

[edit]

The greater DTES area is significantly poorer than the rest of Vancouver, with a median income of $13,691 versus $47,229 for the city as a whole.[118] 53% of the greater DTES population is low-income, compared to 13.6% of the population of Metro Vancouver.[119] In the V6A postal area, whose boundaries are similar to the greater DTES area, 6,339 residents received some form of social assistance in 2013.[120] Of these, 3,193 were considered disabled and 1,461 were considered "employable". The base welfare rate for single adults who are considered employable is $610 per month: $375 per month for shelter and $235 ($335 since July 2017) per month for all other expenses.[120] Advocates for low-income DTES residents say this amount, which has not increased since 2007, is not enough to live on.[121][122] In 1981, the base welfare rate was equivalent to $970 per month after adjustment for inflation.[122]

Some DTES residents supplement their incomes through the informal economy, through volunteer work which can yield stipends,[120] or through criminal activity or sex work.[123] A 2008 survey of SRO residents found that the average tenant income from all sources, including the informal economy, was $1,109 per month.[86]

In addition to addiction and mental illness issues, DTES residents often have difficulty finding employment due to mental and physical disabilities and a lack of education and skills.[124] According to a 2009 survey of the 30 blocks in and around the DTES, 62% of the residents over the age of 15 were not considered participants in the labour force, compared to 33% in Vancouver as a whole.[52]

The DTES is often referred to as "Canada's poorest postal code," although this is not the case.[125]

Housing

[edit]Both homelessness and substandard housing are major issues in the DTES that compound the neighbourhood's problems with addiction and mental illness. In 2012, there were 846 homeless people in the greater DTES area, including 171 who were not in some form of shelter.[126] The DTES homeless made up approximately half of the city's total homeless population,[121] over a third of whom are Indigenous.[127]

Thousands of DTES residents live in SROs, which provide low-cost rooms without private kitchens or bathrooms,[59] Although conditions in SROs vary considerably, they have become notorious for their squalor and chaos. Many are over 100 years old and in extreme disrepair, with shortages of necessities such as heat and functioning plumbing. In 2007, it was reported that four out of five rooms had bed bugs, cockroaches, and fire code violations.[20] Even at their best, the SROs lack living space, resulting in tenants spending more time in the public areas of the DTES, including its street-based drug scene.[45]

SRO landlords have often been called "slumlords" for failing to fix problems and illegally evicting tenants.[128][129] The city has often been slow to force SRO owners to make significant repairs, saying that owners could not afford to make them without raising rents and adversely affecting affordability.[130]

Housing availability and affordability

[edit]Any discussion of improving the continuum of care for addiction must include housing as an essential component, particularly for the most vulnerable individuals coping with homelessness, addiction, and mental illness.

— B.C. Medical Association, [88]

The City refers to the housing and homelessness situation in the DTES as a "crisis".[131] There is wide support amongst governments, experts, and community groups on a Housing First model, which prioritizes stable, quality housing as a precursor to other interventions for the homeless, those who use drugs, or those with mental illness.[88] Many people with severe addiction or mental illness require supportive housing.[132]

As the DTES has many low-income adults who live alone and are at risk of homelessness, trends in housing options for low-income adults are of central importance to the neighbourhood. Although SROs have well-known problems, each SRO resident who loses their room and ends up on the street costs the provincial government approximately $30,000 to $40,000 per year in additional services.[133]

In recent years, the number of units designed for low-income singles has increased slightly: In the downtown area (Burrard Street to Clark Drive), there were 11,371 units in 1993 and 12,126 units in 2013.[134] The number of privately owned SROs declined during this time by 3283 units, while the number of social housing units increased by 4038 units.[134] In 2014, 300 privately owned SRO units were lost.[135]

However, rents in many of those units have risen. Rents in social housing units for low-income singles are fixed at the shelter component of welfare rates, but rents in privately owned SROs can vary. In 2013, 24% of privately owned SROs rented at the base welfare shelter rate of $375 per month, down from 60% in 2007.[135] According to one advocacy group, the average lowest rent in privately owned hotels in the greater DTES area was $517 per month in 2015, and no vacant rooms were rented at less than $425 per month.[136]

The city has implemented a bylaw to discourage the redevelopment of SROs.[137] Advocates for SRO tenants argue that the city's bylaw does not go far enough, as it does not prevent rent increases.[137] The city says that only the province, not the city, has the jurisdiction to control rents and that the province should raise welfare rates.[138]

Since 2007, the provincial government has acquired 23 privately owned SRO hotels in the greater DTES area, containing 1,500 units. It undertook extensive renovations in 13 buildings for $143.3 million, of which $29.1 the federal government paid million.[46] Due to rising rents and often-decrepit conditions in the area's remaining 4,484 privately owned SROs, DTES activists have called for governments to replace them with a further 5,000 social housing units for low-income singles.[139]

Health and well-being

[edit]A 2013 study of SRO residents in the greater DTES area found that 18.4% were HIV positive and 70.3% were positive for hepatitis C.[53] Few of those infected with hepatitis C receive treatment.[53][140] The DTES population also has higher rates of tuberculosis and syphilis than the rest of the province,[141] and injection drug users are susceptible to other infections such as endocarditis.[142] Indigenous people are at the greatest risk from the disease.[143]

Amongst the most vulnerable DTES residents, common issues with psychosocial well-being include low self-worth, lack of personal safety, lack of respect from others, social isolation, and low education levels.[143][144] Many have lost custody of their children.[145] A 2000 report from the Vancouver Native Health Society Medical Clinic said, "Many individuals are survivors of severe childhood trauma. Negative experiences such as family violence, parental substance abuse, sexual and emotional abuse, suicide, divorce, and residential school atrocities are the norm."[143] Many DTES residents are too unstable to keep appointments or reliably take medication.[144]

Life expectancy in the greater DTES area is 79.9 years, a significant improvement since the mid-1990s.[44] Some of the increase may, however, be explained by the migration of healthier residents to the neighbourhoods surrounding the DTES.[44] A 2015 study of DTES SRO residents found that they were eight times more likely to die than the national average, mostly due to psychosis and hepatitis C-related liver dysfunction.[140]

Costs

[edit]

Several overlapping sets of data exist on costs related to the DTES:

- DTES-specific costs: Of the estimated $360 million per year to operate 260 social services and housing sites in the greater DTES area, three-quarters of the spending is funded by governments, and the rest by private donors.[6] This figure includes operating costs of a range of organizations, including neighbourhood health care services, but does not include standard city operations, the capital costs of building social housing or other infrastructure, or hospital costs.[6]

- Wider-area costs related to issues concentrated in the DTES: In the closest hospital to the DTES, Saint Paul's, injection drug use leads to approximately 15% of admissions.[142] The annual cost of ambulances responding to overdoses in Vancouver is $500,000,[142] and the cost of police response to calls involving mental health problems is estimated to be $9 million per year.[92]

- Costs per individual: For each untreated drug addict, the costs to society, including crime, judicial costs, and health care, are estimated to be at least $45,000 annually.[146] The government-paid lifetime healthcare cost per HIV-infected injection drug user is estimated at $150,000.[142] A 2008 study estimated that each homeless person in B.C. costs $55,000 per year in government-paid costs related to healthcare, corrections, and social services, whereas providing housing and support would cost $37,000 per year.[55] Costs per individual vary widely: A 2016 study found that 107 chronic offenders in the DTES incur public service costs of $247,000 per person per year.[80]

Law enforcement

[edit]For the police, success is measured in how well the drugs are kept corralled on Hastings between Cambie and Main, where they can expect the fewest complaints. Arrests are infrequent, and when they occur, they are counterproductive... Like a hydra, direct enforcement paradoxically crowds the streets with the incarcerated dealers multiplying replacements.

— Reid Shier, former DTES art gallery director / curator, [26]

In comparison to other Canadian cities, the VPD is generally considered to be progressive in dealing with drugs and sex work,[147] emphasizing harm reduction over law enforcement.[148]

The VPD engages in the controversial practice known as "carding," or "street checks," in which police stop and question individuals whom they suspect of being involved in criminal or suspicious activity. In Vancouver, 15% of street checks are on Indigenous people, representing just 2% of the general population, and 5% of reviews are on Black people, representing less than 1%. Some civil rights groups believe the VPD's practices constitute racial profiling and result in excessive harassment and violence against Indigenous and Black residents.[149]

Since the 1980s, the VPD has ignored drug use in the DTES, as the sheer volume of users makes it unfeasible to arrest all of them.[31] A large-scale police crackdown on DTES drug users in 2003 made no difference except to displace drug use to adjacent neighbourhoods.[150] To encourage people to call for help when a drug user is overdosing, paramedics rather than police respond to 911 calls about overdose deaths, except in cases where public safety is at risk.[31]

Nationwide efforts to reduce the supply of drugs through law enforcement have had minimal impact on the easy availability or low prices of illicit drugs in Vancouver.[45] By former mayor Mike Harcourt's estimate, police intercept only 2% of the drugs that enter the city.[151] Vancouver police guidelines on dealing with sex workers emphasize focusing on addressing violence, human trafficking, and involvement of youth or gangs in prostitution, whereas sex involving consenting adults is not an enforcement priority.[147][152]

Relations between police and DTES women were strained by police shortcomings that allowed serial killer Robert Pickton to prey on the community for years before he was arrested in 2002; the VPD apologized in 2010 for its failures in apprehending him.[153] In 2003, the Pivot Legal Society filed 50 complaints from DTES residents alleging police misconduct.[154] An investigation by the RCMP, in which several VPD officers and the police chief failed to co-operate, found that 14 of those allegations were substantiated.[154] In 2007, Pivot agreed to withdraw its remaining complaints, following apologies and changes to VPD policies and procedures.[further explanation needed][155]

In 2008, the VPD implemented a crackdown on minor offences, such as illegal vending on sidewalks and jaywalking. The ticketing blitz was stopped after objections from community groups. Residents with unpaid tickets – particularly women and sex workers – would be less afraid to approach the police to report serious safety concerns.[156]

In 2010, police launched an initiative to combat violence against DTES women that resulted in the convictions of several violent offenders.[157] However, the level of trust toward police remains low.[153] According to some DTES activists, "gentrification / condos and police brutality," rather than drugs, are the two worst problems in the neighbourhood.[158]

Controversies

[edit]Concentration of services controversy

[edit]You keep dumping money in, building social housing and filling it up with people from all around the region and the country ... they all get chemically dependent, and it's just more sales for the drug dealers.

— Philip Owen, former Vancouver mayor, [48]

The Downtown Eastside has become the last place where everybody runs to from across Canada. It's the last, best place for people who are the most marginalized people in the country.

— Karen Ward, DTES resident, [159]

It's the NIMBYism of the other 23 communities in the city that is the Downtown Eastside's greatest problem. And the city needs to work to put significantly more services in different communities.

— Scott Clark, Aboriginal Life in Vancouver Enhancement Society, [160]

The DTES is the site of many service offerings, including social housing, health care, free meals and clothing, harm reduction for drug users, housing assistance, employment preparation, adult education, children's programs, emergency housing, arts and recreation, and legal advocacy.[6] In 2014, the Vancouver Sun reported that there were 260 social services and housing sites in the greater DTES area, spending $360 million per year.[6] No other Canadian city has concentrated services to this degree in one small area.[6]

Proponents of the high level of services say that it is necessary to meet the complex needs of the DTES population.[6] For some residents, the sense of community and acceptance that they find in the DTES makes it a unique place of healing for them.[132]

Locating many services in the DTES has also been criticized for attracting vulnerable people to an area where drugs, crime, and disorder are entrenched. Some advocates for vulnerable populations believe that many DTES residents would have a better quality of life and improved chances of health if they could separate from the neighbourhood's predatory drug pushers and pimps.[48][112][132][161]

During the city's 2014 planning process for the greater DTES, two-thirds of those who participated said they wanted to stay in the area.[6] But a 2008 survey of SRO tenants had indicated that 70% wanted to leave the DTES.[86] The city's 30-year plan is for two-thirds of the city's future social housing to be located in the greater DTES area.[6]

Views on services in other neighbourhoods

[edit]Vancouver Coastal Health says that the lack of appropriate care for complex social and health issues outside of the DTES often does not allow people "the choice to remain in their home community where their natural support systems exist... A common barrier that prevents mentally ill and addicted people from living outside of the DTES is a lack of appropriate services and support. Too often, clients who secure housing outside the neighbourhood return to the DTES regularly because of the lack of support in other communities."[56]

Proposals to add social housing and services for those with addiction or mental health issues to other Metro Vancouver neighbourhoods are often met with Nimbyism, even when residents selected for such projects would be low-risk individuals.[162] A 2012 poll of Metro Vancouver residents found that although nine out of 10 of those surveyed wanted the homeless to have access to services they need, 54% believed that "housing in their community should be there for the people who can afford it."[163] Some commentators have suggested that Vancouver residents tacitly agree to have the DTES act as a de facto ghetto for the most troubled individuals in the city.[160]

Gentrification controversy

[edit]This community could be wiped off the face of the map. The neighbourhood's character has changed in the last three or four years. Affordable rentals are a thing of the past.

— Harold Lavender, DTES resident, [164]

Years of experience in other urban centres make it clear that maintaining the DTES as a high or special needs social housing enclave, over the long term, will not help to stabilize either the community or the city as a whole.

— Strathcona Business Improvement Association, Ray-Cam Community Association, and Inner City Safety Society, [116]

The DTES lies a few blocks east of the city's most expensive commercial real estate.[26] Since the mid-2000s, new development in the DTES has brought a mixture of market-rate housing (primarily condominiums), social housing, office spaces, restaurants, and shops.[165] Property values in the DTES area increased by 303% between 2001 and 2013.[166] Prices at the newer retail establishments are often far higher than low-income residents can afford.[165]

The city promotes mixed-income housing, and requires new large housing developments in the DTES to set aside 20% of their units for social housing.[165] As of 2014, in a section of Hastings Street from Carrall Street to Heatley Avenue, at least 60% of units must be dedicated to social housing and the rest must be rental units.[167] Rents in at least one-third of new social housing units are not permitted to exceed the shelter component of welfare rates.[167]

Proponents say that new developments revitalize the area, improve the quality of life, provide new social housing, and encourage a stronger retail environment and a stabilizing street presence.[61][165] They emphasize that their goal is for the DTES to include a mixture of income levels and avoid the problems associated with concentrated poverty, not to become an expensive yuppie-oriented neighbourhood like nearby Yaletown.[61][168][169]

Others oppose the addition of market housing and upscale businesses to the DTES, in the belief that these changes will drive up prices, displace low-income residents, and make poor people feel less at home.[61][170] Protests against new businesses and housing developments have occasionally turned violent.[139]

Strategies

[edit]Housing strategies

[edit]

Although housing and homelessness are often perceived as municipal issues, social housing is traditionally funded primarily by senior levels of government, which receive 92% of tax revenue in Canada.[55] Libby Davies, a former DTES activist and Member of Parliament, called for a National Housing Strategy in 2009, saying that Canada is the world's only industrialized country with no national housing plan.[132]

In 2014, the City of Vancouver approved a 30-year plan for the greater DTES area. It sets out a goal of having 4,400 units of social housing added to the greater DTES area, 3,350 units of social housing added elsewhere in the city, and 1,900 units of new supportive housing scattered throughout the city.[172][173] The cost of implementing the plan is estimated at $1 billion, of which $220-million would be paid by the city, $300-million by developers, and more than $500-million from the provincial or national governments.[173] The provincial government, which recently invested $300 million in social housing in Vancouver, said it will not fund the proposed housing expansion and that its housing strategy had shifted towards other models such as rent assistance rather than construction.[174]

Addiction and mental illness strategies

[edit]In 2001, the city adopted a "Four Pillars" drug strategy consisting of four equally important "pillars": prevention, treatment, enforcement, and harm reduction. Advocates of the Four Pillars strategy say that the 36 recommendations associated with the policy have only been partially implemented, with prevention, treatment, and harm reduction all being underfunded.[41] Across Canada, 94% of drug strategy dollars are spent on enforcement.[142] The city's 2014 Local Area Plan for the DTES does not propose solutions to the neighbourhood's drug problems; an article in the National Post described it as a "221-page document that expertly skirted around any mention of the Downtown Eastside as a failed community in need of a drastic turnaround."[48]

The VPD, B.C. Medical Association and the City of Vancouver have asked the province to urgently increase capacity for treating addiction and mental illness.[81][88] In 2009, the BCMA asked that detoxification be available on demand, with no waiting period, by 2012.[88] A 2016 study of youth who used illicit drugs in Vancouver indicated that 28% had tried unsuccessfully to access addiction treatment in the previous 6 months, with the lack of success primarily due to being placed on waiting lists.[175]

After the city and police department described an emerging mental health crisis in Vancouver in 2013, the province implemented three of their five recommendations within a year, including new Assertive Community Treatment teams and a nine-bed urgent care facility at St. Paul's Hospital.[176] In response to a recommendation that the province adds 300 new long-term health care beds for the most severely mentally ill, provincial Health Minister Terry Lake said that more research was needed to determine whether these beds were urgently needed.[176] As of 2015, the province had opened or committed to only 50 new beds.[177]

Co-ordination of services

[edit]Although DTES residents often have a complex combination of needs, services are typically delivered from the perspective of a single discipline (such as police or medical) or a particular agency's mandate, with little communication between the service providers who are working with a given individual.[178] Despite widespread agreement in principle that a coordinated approach is necessary to improve conditions for DTES residents, the three levels of government have not agreed on any overall long-term plan for the DTES, and there is no overall co-ordination of services for the area.[48]

In 2009, the VPD proposed creating a steering committee of senior city and provincial stakeholders, which would be mandated to improve collaboration between service providers to enable a client-centric rather than a discipline-centric model.[179] The report recommends prioritizing the needs of the most vulnerable individuals in the neighbourhood, saying that having them get the assistance they require is "a necessary condition for other neighbourhood improvement initiatives to succeed."[178]

In 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, a Coordinated Community Response Network was formed to distribute funds, resources, and support in the neighbourhood.[180] The network consists of a coordinated effort of over 50 social service and frontline organizations and groups.

Notable activists

[edit]- Shirley Chan, a prominent community activist and co-founder of the Strathcona Property Owners and Tenants Association (SPOTA), has worked for decades to revitalize Chinatown and preserve historical sites in the neighbourhood from development.[181]

- Bruce Eriksen (1928–1997), founder of the Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA)

- Bud Osborn (1947–2014) and Ann Livingston, co-founders of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU)

Portrayals in media

[edit]Films set in the Downtown Eastside include On the Corner, The Ballad of Oppenheimer Park, and Luk'Luk'I. The Matthew Good album Vancouver was inspired by the Downtown Eastside.[182]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 1.

- ^ Nagy, Melanie (27 May 2021). "SisterSpace: Canada's first and only overdose prevention site for women is saving lives". CTV News. Archived from the original on 28 May 2021. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Mauboules, Celine (7 October 2020). Homelessness & Supportive Housing Strategy (PDF) (Report). City of Vancouver. p. 28.

- ^ "Aboriginal Health & Safety". WISH Drop-In Centre Society. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Brend, Yvette (5 April 2018). "B.C. has country's highest rate of police-involved deaths, groundbreaking CBC data reveals | CBC News". CBC News.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Culbert, Lori; McMartin, Peter (27 June 2014). "Downtown Eastside: 260 agencies, housing sites crowd Downtown Eastside". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Matas, Robert (13 March 2009). "B.C. Premier's Olympic plan worries activists". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, Preface.

- ^ Walling, Savannah. "Take a Walk on the Downtown Eastside". Heart of the City Festival. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Gee, Marcus (9 November 2018). "What I saw in a day on the Downtown Eastside shocked me". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Steffenhagen, Janet (8 December 2006). "Our four blocks of hell". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ a b Asfour, John Mikhail; Gardiner, Elee Kraljii, eds. (2012). "Introduction". V6A: Writing from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press. ISBN 9781551524634.

- ^ a b Lupick, Travis (2 October 2016). "10 years of police data reveals how gentrification has affected crime in the Downtown Eastside". The Georgia Straight. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2014, pp. 55–56.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2014, p. 18.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2013, p. 80.

- ^ Atkin, John (1994). "Introduction". Strathcona: Vancouver's First Neighbourhood (first ed.). Vancouver: Whitecap Books Ltd. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-55110-255-9.

- ^ "Strathcona North of Hastings". Heritage Vancouver. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2014, p. 58.

- ^ a b Paulsen, Monte (29 May 2007). "Vancouver's SROs: 'Zero Vacancy'". The Tyee. Vancouver. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ a b City of Vancouver 2014, p. 17.

- ^ "Demolish City's Skid Road, Murder Protest Demands". Vancouver Sun. 6 April 1962. p. 1.

- ^ a b Douglas 2002, chapter 1.

- ^ Mackie, John (19 February 2014). "Japantown: Vancouver's lost neighbourhood". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Mackie, John (18 October 2008). "Carrall Street: Home to some of Vancouver's coolest bars, a stone's throw away from crackheads". The National Post. Toronto. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Douglas 2002, Introduction.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 6.

- ^ Baker, Rafferty (4 May 2016). "Expo 86 evictions: remembering the fair's dark side". CBC News. Toronto. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ a b Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 3.

- ^ Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 10.

- ^ a b c d e Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 13.

- ^ Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, p. 157.

- ^ Patterson, Michelle (Summer 2007). "The Faces of Homelessness Across BC" (PDF). Visions. 4 (1): 7–8.

- ^ "Feb 14th Annual Womens Memorial March". 14 Feb Annual Womens Memorial March. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Fong, Petti (17 December 2002). "Robert Pickton: Missing women inquiry concludes bias against victims led to police failures". Toronto Star. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Elien, Shadi (13 February 2009). "Women's Memorial March to take place on Valentine's Day". The Georgia Straight. Vancouver. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ a b McNeil, Donald G. Jr. (7 February 2011). "An H.I.V. Strategy Invites Addicts In". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 5.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, pp. 26–27.

- ^ MacQueen, Ken (20 July 2015). "The science is in. And Insite works". Maclean's. Toronto. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Katic, Gordon; Fenn, Sam (5 September 2014). "Vancouver's Addiction Ambitions, Revisited". The Tyee. Vancouver. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Point for point: Canada's needle exchange programs". CBC News. Toronto. 27 October 2004. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 7.

- ^ a b c MacQueen, Ken (15 October 2012). "Vancouver's Downtown Eastside gets a new lease on life". Maclean's. Toronto. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f "Drug Situation in Vancouver, 2nd Edition" (PDF). British Columbia Centre of Excellence in HIV/AIDS (2nd ed.). Urban Health Research Initiative of the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b Morton, Brian (28 February 2015). "Downtown Eastside tenants love their renovated SRO suite". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b Matas, Robert (13 February 2009). "The Money Pit". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Hopper, Tristin (14 November 2014). "Vancouver's 'gulag': Canada's poorest neighbourhood refuses to get better despite $1M a day in social spending". National Post. Toronto. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Quinn, Stephen (14 March 2014). "Downtown Eastside redevelopment debate is the same old game". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2013, p. 6.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2013, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Brethour, Patrick (13 February 2009). "Exclusive demographic picture: A comparison of key statistics in the DTES, Vancouver, B.C. and Canada". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Vila-Rodriguez, Fidel; Panenka, William J. (1 December 2003). "The Hotel Study: Multimorbidity in a Community Sample Living in Marginal Housing". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (12): 1413–1422. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12111439. PMID 23929175.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 16.

- ^ a b c "Downtown Eastside Second Generation Health System Strategy" (PDF). Vancouver Coastal Health. 24 February 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Maté, Gabor (24 January 2016). "Opinion: Health-care system poorly understands our addicts and mentally ill". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Woo, Andrea (7 January 2016). "Half of Downtown Eastside's homeless residents came from other areas: study". CBC News. Toronto. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ a b Lupick, Travis (10 August 2013). "Study finds steep drug and mental health challenges for Downtown Eastside single-occupancy tenants". The Georgia Straight. Vancouver. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Cran & Jerome 2008, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e "Vancouver Downtown Eastside Putting it All Together: Plans Policies, Programs, Projects, and Proposals: A Synthesis" (PDF). Building Community Society of Greater Vancouver. July 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2014, p. 50.

- ^ a b Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 2.

- ^ Cran & Jerome 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Cran & Jerome 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Cran & Jerome 2008, p. 10.

- ^ a b City of Vancouver 2013, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Denis, Jen St (9 February 2021). "A 'Family' of Artists of the Downtown Eastside". The Tyee. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2014, pp. 143–147.

- ^ Cheung, Christopher (11 September 2020). "The Downtown Eastside? 'There's a Heartbeat Down Here'". The Tyee. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Lennie, Linda (22 July 2021). "Marcel Mousseau Made the Downtown Eastside Market a Welcoming Space". The Tyee. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Cole, Yolande (7 May 2014). "Downtown Eastside poet and activist Bud Osborn remembered as "hero"". The Georgia Straight. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Denis, Jen St (26 October 2021). "Storytelling Takes Centre Stage at Vancouver's Heart of the City Festival". The Tyee. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Dyck, Bruce Daniel (23 February 2018). Three reincarnations of the Smilin' Buddha Cabaret: Entertainment, gentrification, and respectability in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside 1952–84 (M.A. thesis). Simon Fraser University. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021 – via dtesresearchaccess.ubc.ca.

- ^ Hughes, Josiah (5 October 2020). "Artists from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside Come Together for '100 Block Rock' Compilation". Exclaim!. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Bishop, Greg (4 February 2010). "In the Shadow of the Olympics". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ^ Wilson-Bates 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Wilson-Bates 2008, p. 54.

- ^ Regional Mental Health & Addiction Program (November 2013). Improving health outcomes, housing and safety: Addressing the needs of individuals with severe addiction and mental illness (PDF) (Report). Vancouver Coastal Health. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ a b Woo, Andrea (6 January 2016). "Vancouver subset struggling to escape corrections system's 'revolving door,' study says". The Globe and Mail. Toronto.

- ^ a b Wilson-Bates 2008, p. 22.

- ^ Luk, Vivian (13 October 2013). "How drugs, lack of safe housing fuel Vancouver's mental-health crisis". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Mirchandani, Rajesh (10 February 2010). "Vancouver: 'Drug Central' of North America". BBC News. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Geordon, Omand (22 May 2016). "Little if any heroin left in Vancouver, all fentanyl: drug advocates". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Ellis, Erin; Lindsay, Bethany (14 April 2016). "B.C. declares public health emergency after fentanyl overdoses". Vancouver Sun.

- ^ a b c d Lewis, Martha; Boyes, Kathleen; McClanaghan, Dale; Copas, Jason (April 2008). Downtown Eastside Demographic Study of SRO and Social Housing Tenants (PDF) (Report). Vancouver Agreement. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b City of Vancouver 2013, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d e Stepping Forward – Improving Addiction Care in British Columbia (PDF) (Report). British Columbia Medical Association. March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ a b Matas, Robert (6 September 2012). "Tackling chronic offenders key to reducing Vancouver's high crime rates". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Krishnan, Manisha (8 March 2016). "We Asked Drug Addicts How Much Their Habit Costs Them". Vice News. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Wilson-Bates 2008, p. 12.

- ^ a b Wilson-Bates 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b Cole, Yolande (13 September 2013). "Vancouver police and mayor issue recommendations to address mental health "crisis"". The Georgia Straight. Vancouver. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General (16 August 2019). British Columbia Coroners Service Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC January 1, 2009 – June 30, 2019 (PDF). Government of British Columbia (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ Stewart, Mayor Kennedy (14 December 2018). Mayor's Overdose Emergency Task Force – Recommendations for Immediate Action on the Overdose Crisis – RTS 12926 (PDF) (Report). Vancouver City Council. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- ^ Ministry of Public Safety & Solicitor General (19 November 2020). "British Columbia Coroners Service Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC January 1, 2010 – September 30, 2020" (PDF). Government of British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ^ Dobell Advisory Services Inc and DCF Consulting Ltd (5 March 2007). Vancouver Homelessness Funding Model: More than just a warm bed (PDF) (Report). City of Vancouver. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Hutchinson, Brian (16 March 2012). "Years after Pickton's arrest, the killings have stopped in the Downtown Eastside, the violence has not". National Post. Toronto. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b c Vancouver Police Department 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Keller, James (6 September 2012). "Prostitutes' only relief, inquiry hears, is self-medication with drugs". Maclean's. Toronto. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ a b c City of Vancouver 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Alarcon, Krystal (4 March 2013). "Angel's Story: Trapped in a Violent World". The Tyee. Vancouver. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Vancouver's Anti-Sex Work Gentrification Projects are a Form of Imperialism". The Volcano. 17 May 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Lyons, Tara (2017). "The impact of construction and gentrification on an outdoor trans sex work environment: Violence, displacement and policing" (PDF). Sexualities. 20 (8): 881–903. doi:10.1177/1363460716676990. PMC 5786169. PMID 29379380. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Sex Workers United Against Violence; Allan, Sarah; Bennett, Darcy; Chettiar, Jill; Jackson, Grace; Krüsi, Andrea; Pacey, Katrina; Porth, Kerry; Price, Mae (2020). "My Work Should Not Cost Me My Life" (PDF). The Case against Criminalizing the Purchase of Sex in Canada. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ "Women working in Vancouver sex trade were seen as "disposable," inquiry hears – NEWS 1130". www.citynews1130.com. Retrieved 6 April 2021.

- ^ Rossi, Cheryl (28 February 2014). "Downtown Eastside: The neighbourhood at a glance". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Martin, Carol Muree; Walia, Harsha (4 November 2019). "Red Women Rising: Indigenous Women Survivors in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside". open.library.ubc.ca. doi:10.14288/1.0378104.

- ^ "Police bust drug ring that used torture, terror". CTV News. Toronto. The Canadian Press. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ a b Turpel-Lafond, Mary Ellen (May 2015). Paige's Story – Abuse, Indifference and a Young Life Discarded (PDF) (Report). B.C. Representative for Children and Youth. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, p. 24.

- ^ "Safety in Vancouver". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, pp. 22–24.

- ^ a b Strathcona Business Improvement Association, Ray-Cam Community Association, and Inner City Safety Society (2012). "Vancouver's Downtown Eastside: A Community in Need of Balance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Hotel Empress". Canada's Historic Places. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2013, p. 12.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2013, p. 11.

- ^ a b c City of Vancouver 2013, p. 13.

- ^ a b Lupick, Travis (6 January 2016). "Downtown Eastside activists fear 2016 will see a spike in Vancouver homeless". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ a b Christopher, Ben (10 September 2012). "A Tyee Series Jean Swanson's Advocacy for Vancouver's Impoverished". The Tyee. Vancouver. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, p. 21-26.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, pp. 18.

- ^ Skelton, Chad (10 February 2010). "Is Vancouver's Downtown Eastside really "Canada's poorest postal code"?". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2013, p. 24.

- ^ Thompson, Matt. Vancouver Homeless Count 2016 (PDF) (Report). City of Vancouver. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- ^ Colebourn, John (10 July 2016). "'They thought I was going to back down and leave': DTES tenant's court case shines a light on practices of Sahota landlords". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Cole, Yolande (29 June 2011). "Lawsuit launched against Downtown Eastside building owners". The Georgia Straight. Vancouver. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ "Kerry Jang on city's broken-down SROs: 'There's only so much we can do". CBC News. Toronto. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2014, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 17.

- ^ Project Report: SRO Renewal Initiative (PDF) (Report). Partnerships British Columbia. June 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ a b Housing & Homelessness Strategy Targets 2012–2014 2012 Report Card (PDF) (Report). City of Vancouver. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ a b 2015 Report on Homelessness and Related Actions on SRO (PDF) (Report). City of Vancouver. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Swanson, Jean; Chan, King-mong; Wallstam, Maria (2016). Our Homes Can't-Wait: CCAP's 2015 Hotel Survey and Housing Report (PDF) (Report). Carnegie Community Action Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ a b Lee, Jeff (21 July 2015). "Vancouver introduces harsh SRO rules to dissuade owners from 'renovicting'". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Murphy, Meghan (24 April 2014). "Renovictions on Vancouver's Downtown Eastside Aren't Stopping Anytime Soon". Vice News. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ a b Kane, Laura (26 May 2013). "Vancouver's vision for Downtown Eastside stokes anti-gentrification protests". Toronto Star. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ a b Mercier, Stephanie. "Vancouver's Downtown Eastside residents dying at 8 times the national average". CBC News. No. 10 September 2015. Toronto. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Wood, Evan; Kerr, Thomas; Spittal, Patricia M.; Tyndall, Mark W.; O'shaughnessy, Michael V.; Schechter, Martin T. (April 2003). "The health care and fiscal costs of the illicit drug use epidemic: The impact of conventional drug control strategies". BC Medical Journal. 45 (3): 128–134. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Adilman, Steve, MD; Kliewer, Gordon, RN (November 2000). "Pain and wasting on Main and Hastings: A perspective from the Vancouver Native Health Society Medical Clinic". British Columbia Medical Journal. 42 (9): 422–425.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Campbell, Boyd & Cutbert 2009, chapter 4.

- ^ Wilson-Bates 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Ellis, Erin (7 April 2016). "Injecting common painkiller an alternative to heroin, Vancouver study finds". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ a b Li, Wanyee (5 December 2014). "Vancouver police to prioritize safety over anti-prostitution laws". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Vancouver Police Department Drug Policy" (PDF). Vancouver Police Department. September 2006.

- ^ Prystupa, Mychaylo (14 June 2018). "Blacks, Indigenous over represented in Vancouver police stops: 10 years of data". CTV News.

- ^ Wood, Evan; Spittal, Patricia M.; Small, Will; Kerr, Thomas; Li, Kathy; Hogg, Robert S.; Tyndall, Mark W.; Montaner, Julio S.G.; Schechter, Martin T. (11 May 2004). "Displacement of Canada's largest public illicit drug market in response to a police crackdown". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (10): 1551–1556. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1031928. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 400719. PMID 15136548.

- ^ Cameron, Ken; Harcourt, Mike (2009). City Making in Paradise: Nine Decisions that Saved Vancouver. D & M Publishers. p. 198.

- ^ Rossi, Cheryl (22 March 2012). "Advocates laud new Vancouver police 'sex work' guidelines". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b Stueck, Wendy (25 April 2016). "SisterWatch initiative has not built trust between police, DTES: report". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ a b Theodore, Terri (17 March 2009). "Allow police misconduct hearings, legal group urges judge". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. The Canadian Press. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- ^ "Activists reach a pact with police over Downtown Eastside issues; New procedures erase the list of complaints". The Province. Vancouver. 6 November 2007. p. A7.

- ^ Howell, Mike (21 January 2014). "Vancouver Police Department sidesteps stance on DTES jaywalkers". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Project Sister Watch". Vancouver Police Department. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ^ Swanson, Jean (24 October 2009). "Residents suggest solutions to Downtown Eastside problems". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ Lupick, Travis (9 April 2014). "Downtown Eastside residents fear dispersal due to Local Area Plan". The Georgia Straight. Vancouver. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ a b McMartin, Pete (27 June 2014). "Pete McMartin: Vancouver's Downtown Eastside is a ghetto made by outsider". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Benoit, Ceclia; Dena, Caroll (1 March 2001). "Marginalized Voices From The Downtown Eastside: Aboriginal Women Speak About Their Health Experiences" (PDF). The National Network on Environments and Women's Health, York University. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Ludvigsen, Mykle (Summer 2005). "Not in My Backyard: Nimby alive and well in Vancouver" (PDF). Visions. 2 (6): 15–16.

- ^ Woo, Andrea (4 October 2012). "NIMBYism based on 'fear of the unknown". The Globe and Mail. Toronto.

- ^ Colebourn, John (20 March 2016). "Low-income rental units drying up in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Vancouver's Downtown Eastside feeling gentrification squeeze". CBC News. Toronto. The Canadian Press. 26 December 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ^ Downtown Eastside Social Impact Assessment – Draft Report (PDF) (Report). City of Vancouver. 15 February 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ^ a b Robinson, Matthew (15 March 2014). "Vancouver's $1-billion Downtown Eastside plan approved by council". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Mickleburgh, Rod (14 March 2013). "Mike Harcourt weighs in on delicate issues behind Pidgin protests". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ Mason, Gary (23 October 2008). "Finally, an issue that sets mayoral candidates apart". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Mackie, John (6 March 2014). "The Battle of Hastings: Notorious Vancouver street in for big changes — and conflicts". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ Rossi, Cheryl (28 February 2014). "Downtown Eastside: 'It's just the Ovaltine'". Vancouver Courier. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ City of Vancouver 2014, p. 97.

- ^ a b Dhillon, Sunny (27 February 2014). "Vancouver reveals $1-billion plan for Downtown Eastside revival". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Mackie, John (26 February 2014). "City unveils $1-billion plan for Vancouver's Downtown Eastside". Vancouver Sun. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ DeBeck, Kora; Kerr, Thomas; Nolan, Seonaid; Dong, Huiru; Montaner, Julio; Wood, Evan (6 January 2016). "Inability to access addiction treatment predicts injection initiation among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 11 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s13011-015-0046-x. PMC 4702392. PMID 26733043.

- ^ a b Woo, Andrea (23 October 2014). "A year after Vancouver declares mental health crisis, cases continue to climb". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ Lupick, Travis (19 August 2015). "Vancouver hospitals predict 2015 will see emergency mental-health visits surpass 10,000". The Georgia Straight. Vancouver. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ a b Vancouver Police Department 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Vancouver Police Department 2009, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Hollingdale, Hazel (16 November 2020). CCRN EVALUATION REPORT (PDF) (Report). pp. 2–5. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- ^ Alexander, Don (31 December 2019). "Remembering the legacy of Shirley Chan: Saving Vancouver's Chinatown neighbourhood". doi:10.25316/IR-4290. Retrieved 16 November 2021 – via DTES Research Access Portal.

- ^ Lederman, Marsha (30 October 2009). "Native son Good sings of Vancouver the bad". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

Sources